Some come to praise, some to bury; some to demystify, some to prop up the myth. What all music biographers share is the knowledge that their readership will be drawn mostly from their subject's fan base, and from the more fanatical end at that. So what's the conscientious Boswell, someone aiming for more than either a puff job or a kneejerk bit of iconoclasm, to do? (For a look at the product of a lack of conscience, consult the works of Albert Goldman.) Two recent books, justifiably ballyhooed, provide a good miniature case study by tackling extremely contrasting subjects and achieving similarly compelling results.

Trumpeter and vocalist Chet Baker, forever and misleadingly referred to as the James Dean of jazz, is a mainstay on the kind of lifestyle accessory mood-jazz compilation CDs sold in Starbucks. His musical reputation, based on not much more than a half-dozen albums dating from the fifties, rests on his unique way with a ballad. The young Baker conveyed a poignant wounded intimacy epitomized by his immortal versions, both instrumental and sung, of "My Funny Valentine", a song he pulled out of obscurity. With hindsight it's clear the impact had as much to do with Baker's technical limitations as with any particular skill. As James Gavin quotes Pauline Kael on Baker: "His stoned, introverted tonelessness is oddly sensuous." Kael was commenting on Baker's playing in Bruce Weber's documentary biopic Let's Get Lost, but she could have been encapsulating the contradictions, both musical and personal, that made Baker an icon.

At this point another quote from the book is called for¨this one from Baker's long-suffering girlfriend/ muse Ruth Young: "Chet's aura is overcelebrated. Somehow his lack of personality became his personality." Young hits the nail squarely on the head, and summarizes what Gavin has spent the preceding several hundred pages illustrating: Chet Baker was a blank canvas on which his fans could project what they wished, and the source of that blankness was heroin, which far outpaced music as the driving force in Baker's life from his late teens onward. The operative word in Kael's description, without a doubt, is "stoned."

Such was the extent of Baker's addiction that by 1957, at the height of his poll-winning fame, he was already a shell, scuffling for junk on the streets of Manhattan. He might have bottomed out and been forced to pull himself together; instead, as has many a jazzman, he went to Europe, where the appetite for doomed American romantics was and is insatiable. Buoyed by the Italians and French fawning over his every wobbly note, he was able to sustain a diminishing career through the sixties, seventies and eighties before his spectacularly abused body finally cashed the long-overdue cheque in Amsterdam in 1988.

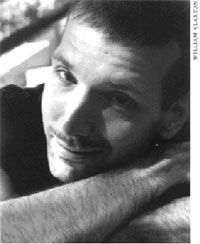

The irony of the James Dean label, then, is that Baker didn't flame out at all but left a decades-long trail of destruction directed both inward and out, a trail this book maps out in harrowing detail. James Ellroy's LA noir tales have nothing on Gavin's straight-ahead cataloguing of Baker's protracted descent. It's hard to imagine anyone's image of Baker as "cool" surviving descriptions of the trumpeter taking the stage in blood-caked trousers, injecting heroin into his groin because that's where the last recognizable veins were, robbing pharmacies then burning them down to hide the evidence, beating up girlfriends, using booze to put his infant son to sleep...the list goes on and even, incredibly, gets worse. But Gavin can't be accused of sensationalism; he's not emphasizing the worst because, as it soon becomes all too clear, the worst was all there was. Yet neither does Gavin, clearly a fan in spite of himself, shortchange the source of Baker's appeal, the reason he's writing the book and we're reading it. The allure of those early recordings, and the never-to-be-discounted impact of those impossibly glamorous William Claxton album cover portraits (where the Dean tag really does make sense) are such that even the horror story of the artist's life can't wipe them out. Gavin's great achievement (in contrast to Weber, whose acclaimed film now looks like a rose-tinted panygeric in comparison) is that neither side of the Baker coin gets cheated. But one suspects Gavin is after something else too, and should even one Starbucks-sipping convert be disabused of the notion of "heroin chic," he'll have gotten it.

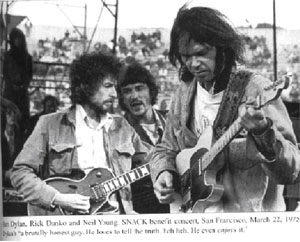

Neil Young is unlike Chet Baker in many ways: his artistic pre-eminence is indisputable (can anyone other than Bob Dylan even stand in the same room with him?); the quality of his output, with exceptions, has been sustained for nearly forty years; where Baker endured constant damning comparisons to Miles Davis, Young is sui generis. Probably most pertinent to Jimmy McDonough's biography is that unlike Baker, Young isn't dead. Far from it. In one of this book's many transcribed cat-and-mouse exchanges between the subject and his "authorized" biographer (never has the term been so loaded with irony) the legendarily evasive and contrary Young hazards a guess as to why his work inspires such intense identification in fans: "That's because it's not so specific that it eliminates them. To write an autobiography would go against the grain of all that."So, too, apparently, would co-operating with one's biographer. McDonough's frustration at Young's slipperiness practically forms a motif for the book, inserted as it is at regular intervals; incredibly, what he manages to reveal is still enough to make his book as epic in length and scope as Neil Young's career.

McDonough, we see from the outset, is determined to get it ALL down. How many biographers would have bothered digging up (and actually reading) father Scott's early novel about the Winnipeg flood, or tracking down the Thunder Bay man who produced a demo by the teenaged Young that prefigures much of his subsequent output? For fans, the lengthy account of Young's Canadian childhood and apprenticeship will be an eye-opening treat, far outstripping previous treatments, including Scott Young's. It's always tempting in biographies of the great and famous to invest every youthful anecdote with looming significance; McDonough resists that, but still gets at the essential Canadianness of his subject, and at the roots of his longevity, tellingly observing how "Scott was¨just as Neil would be¨lucky, adventurous, and driven to the point of mania."

It would take a book-length review just to recap the stages of Young's career and how McDonough chronicles them, so I'll limit myself to a couple.

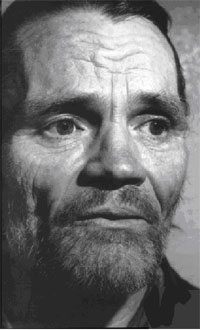

The journey in a hearse from Toronto to California, and the subsequent Icarus-like career of the oh-what-might-have-been Buffalo Springfield (a story fictionalized to great effect in Ray Robertson's riotous novel Moody Food) provide priceless drama and farce. At one point Young's irascible mother, Rassy, berates Stephen Stills for not allowing more of her son's songs in the band's set; at another we're vouchsafed a look into the present life of long-lost genius bassist Bruce Palmer, who appears all but unhinged.

In the most illuminating sections of the book, McDonough digs deep into the early-70s period when Young, fresh from mega-success with the sweetly melodic Harvest and seemingly set for a lucrative run in the middle of the road, pulled a remarkable u-turn and released a series of abrasive and unsettling albums¨Time Fades Away, Tonight's The Night, On The Beach¨that reflected the destructive tendencies just below the surface of the California myth. McDonough finds a fitting metaphor for the mood of the time in a drug dealer's murder in the hippie musician's colony of Topanga Canyon. This incident and others even closer to home¨the deaths of Crazy Horse bandmate Danny Whitten and roadie Bruce Berry, a failing marriage¨affected Young deeply, and his decision to risk career suicide by reflecting his mood in music is probably his greatest achievement. McDonough doesn't come right out and say this, but the space he allocates to this era is acknowledgement enough.

Greatly to McDonough's credit, too, is how he gives full play to the long-running behind-the-scenes figures who've provided the ballast for Young's impulsiveness: manager Elliot Roberts, the late producer/sparring partner David Briggs, maverick mentor Jack Nietzche and especially Crazy Horse, the great loose-cannon innocents of rock and roll whose ongoing 30-year on-off relationship with their boss almost defies belief.

A major caveat: In 1984, Neil Young gave an interview to Britain's New Musical Express. He was in the middle of a reactionary Reaganite phase, and among his pearls was this: "You go to a supermarket and you see a faggot behind the fuckin' cash register, you don't want him to handle your potatoes." It was one of the most despicable things any reputable artist has ever been quoted as saying. For some years after, I couldn't listen to a Neil Young album. (Friends have described reacting similarly; our boycott was probably made easier by the fact that Young's output at the time consisted of a dreary series of genre exercises seemingly designed to annoy his record company; when David Geffen "scandalously" sued Young for delivering unrepresentative product, many of us inwardly cheered.) Surely McDonough, who quotes the comment and often makes a point of his own feistiness, will take Young to task for it? But no, he lets it go with hardly a comment. Strange indeed.

Also on the debit side is that McDonough's passion for Young's early work and the culture from which it sprang has an unfortunate curmudgeonly flipside. As the story proceeds into the nineties and Young's work careens from sustained flashes of genius (Ragged Glory, Sleeps With Angels), maddening water-treading and nostalgia-mongering (Unplugged, Harvest Moon), and failed attempts at hipness (the hookup with Pearl Jam whose title I can't be bothered looking up), McDonough increasingly betrays a sour alienation from contemporary culture. He comments, for example, on how Bob Dylan's 1997 Time Out of Mind album was especially heartening "for those of us who felt that everything was going down the shitter." Well, speak for yourself, sir¨there are those of us who saw Time Out of Mind as one among many great concurrent releases, albums by the likes of Radiohead, Portishead, The Verve, Jeff Buckley, even old geezer Van Morrison. Given Young's stated credo¨"Rock and roll is just a name for the music of the young spirit"¨McDonough's grumpiness is all the more unseemly.

"How do you finish a book about a guy when you feel in your heart he's ignoring his muse?" despairs McDonough in the home stretch, when Young is being especially uncooperative (and musically lazy, preferring to concentrate on his activities as a model train mogul.) The answer, seemingly, is that you don't finish it; interest and anecdote drop off sharply after 1997. But never count Neil Young out: his 2002 album may be a dud, but there's no reason not to think another masterpiece might be just around the corner. Shakey is, to quote its author, "not an obituary but an action painting. Still in progress." It's hard to imagine that anyone who reads it won't gladly sign up for the journey's next leg. ˛